In the first article of this series, we outlined how organisations can establish a clear AI vision, prioritise use cases, and put in place foundational governance structures and enabling technologies. The next steps in the AI adoption journey involve understanding how introducing AI systems can generate risk – in the business processes in which AI will operate and against the individuals AI outputs will affect. Traditional IT risk, privacy and cyber security assessments are essential, but may not adequately capture the unique characteristics of AI.

In this article we will cover the activities to understand AI-related compliance obligations, conducting an AI impact assessment to identify and mitigate risks from AI systems, and making effective approval decisions before commencing AI projects.

When organisations ask, “What laws apply to AI?”, they’re usually asking the wrong question. A better question is: “What is this AI system actually doing, and in which business process?”

Is it supporting recruitment decisions? Drafting correspondence to citizens? Profiling customers for eligibility or risk? Assisting with safety-critical operations? The context of use determines which obligations matter most.

A practical starting point is to map:

Once you have that picture, you can systematically test obligations across a few core domains. For most organisations (especially in the public sector), that includes:

Layered over these, organisations will also have internal requirements such as codes of conduct, data classification standards, acceptable use policies, records management and procurement rules.

A comprehensive mapping of compliance obligations for each AI initiative generally requires input from multiple subject matter experts across an organisation. This often includes consulting with legal, privacy and information governance specialists, people and culture, risk and compliance, cyber security, data and AI engineering teams and the applicable business or service owners.

Once an organisation has identified its obligations, the next step is to systematically assess the risk of each AI system and identify how to manage it. The aim is to create a practical mechanism that helps teams understand where the real risks sit, what to do about them, and when to ask for help.

Triggers: when should an AI impact assessment be required?

An analysis effort of an AI impact assessment needs to be proportionate to the complexity and risk of the project, without creating undue project delivery burden. It should be baked into your project delivery methodology and AI lifecycle with clear triggers, such as:

Clear guidance should be made available to AI system owners, data owners, or project delivery managers to ensure a predictable process can be followed, with relevant subject matter expert engagement and approval stage gates. Without these defined expectations, impact assessments could become a source of delivery delays.

Core components of an AI impact assessment

An AI impact assessment should first establish basic facts about the system and its context. This is where teams describe what the AI system actually does, how it works within the business process, and who will interact with it. Is it predicting, classifying, ranking, generating, or recommending? Are the users internal staff, customers, citizens, or third parties? What kinds of data does it consume and produce, and how sensitive is that information? Is the system hosted in an enterprise cloud or on-premise environment, or via a third-party software-as-a-service platform, and in which countries is the data processed? It is also important to be clear about the provenance of the model itself: whether it is developed in-house, uses open source model packages, or consumed “as-a-service” from a vendor. Two systems that use similar underlying technology can have entirely different risk profiles depending on the business context and deployment model, and the assessment needs to make that visible.

Next, an AI impact assessment should consider how the initiative will realise responsible AI objectives. For accountability, the assessment should tease out who owns the system and its outcomes, who has authority to change the model or its configuration, and how issues will be logged, investigated and resolved in practice. To ensure AI-powered processes provide transparency to users or affected individuals, it should explore how people interacting with the process will be informed that AI is involved, what they will be told about how it works and its limitations, and what avenues exist for them to question or challenge outcomes.

Fairness requires a similarly concrete treatment. Instead of simply asserting that the system will be fair, the assessment should ask whether the AI touches protected attributes or closely related proxies, what testing has been done to detect disparate impacts across different cohorts, and what level of residual disparity the organisation is prepared to tolerate in this specific context. Reliability and safety can be examined by describing what “failure” would look like, what the worst credible outcomes could be, and how the system has been tested before deployment and will be monitored afterwards. The assessment should also consider if the business context requires explainability from AI outputs, and whether business users, regulators and affected individuals could reasonably understand how key decisions or outputs are produced, and whether confidence or uncertainty can be measured.

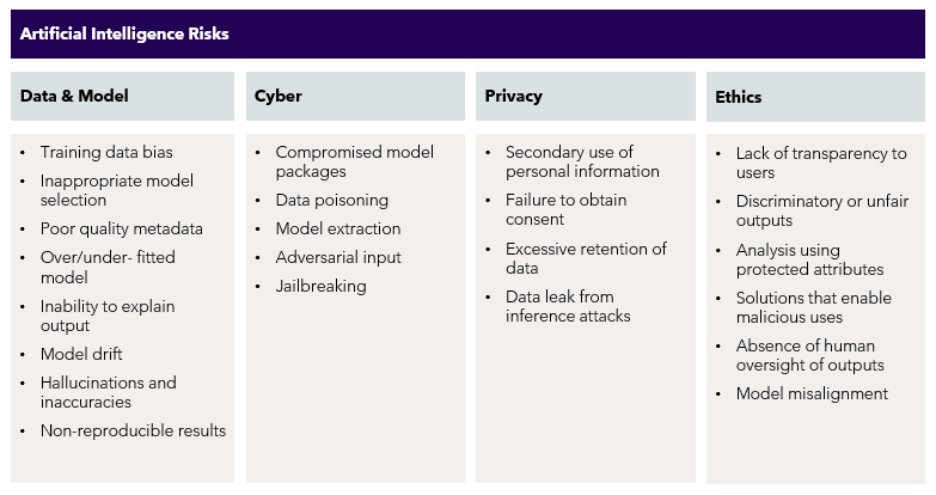

When personal information is involved, the privacy dimension comes to the fore: what personal data is used in training, inputs and outputs, how the organisation minimises collection, how data is protected and retained, and how individuals’ rights to access, correction and deletion are managed. Cyber security is the final critical lens, covering how data is protected in transit and at rest, which AI-specific threats (such as adversarial input, compromised model packages, prompt injection or data poisoning) are relevant, and what assurances the organisation has over the security posture of any third-party vendors or cloud environments involved.

Finally, the assessment must connect the any concerns identified to the organisation’s enterprise risk framework. Here, the focus is on turning qualitative reflections into actionable risk management decisions. For each key theme – fairness, transparency, privacy, cyber security, reliability, and so on – the assessment should describe the specific risk in clear terms and assign an inherent risk rating using the organisation’s standard risk matrix. It should then outline the controls or mitigations that will be put in place: for example, human review steps, access controls, logging and monitoring, data minimisation techniques, additional testing, changes to user guidance, or stronger contractual protections with vendors. Once those controls are defined, the residual risk can be re-rated, and it should be explicit who is accepting that level of risk.

When done well and at the early stages of project initiation, the impact assessment process does more than fulfil compliance requirements; it prompts design changes, influences deployment decisions, and clarifies operating expectations. That is the hallmark of a useful AI impact assessment: it shapes what the organisation builds and ships, rather than simply justifying a decision that has already been made.

In a mature organisation, the AI impact assessment becomes a standard input to your AI Governance Committee (or equivalent forum), sitting alongside vendor assessments, privacy and security reviews, business cases and pilot results. When the committee looks at a proposal, the question it is trying to answer is straightforward: Given the risks we’ve identified, the mitigations we’ve proposed and the capabilities we have today, are we comfortable to proceed – and on what terms?

Using the assessment as a guide, the committee’s role is to probe and challenge. Are the assumptions about accuracy realistic, or is there overconfidence in the model’s performance? Have fairness and bias been tested in a way that makes sense for the people and communities affected? Is the organisation relying heavily on a vendor without having the right transparency, security and contractual protections in place? Are the proposed controls – additional monitoring, human review, training, access controls – practical and funded?

In practice, review of the business case and AI impact assessment results in one of three outcomes: proceed, proceed with conditions, or do not proceed at this time. “Go” means the risks are within appetite and the controls are considered adequate. “Go with conditions” might mean a limited pilot, a narrower use case, or specific mitigations that must be implemented before the system is scaled. “No-go” is not necessarily a failure; it is an indication that, given current capabilities or regulatory uncertainty, the organisation is not yet comfortable to deploy that particular use of AI.

These decisions are shaped by more than the risk assessment itself. Two organisations can look at the same AI use case and reach different conclusions, and both can be making sensible choices. The difference lies in their risk appetite and their AI maturity. An organisation with strong data governance, established model monitoring and a dedicated AI team may be willing to take on initiatives that a less mature organisation would sensibly defer. Good governance involves being honest about this. Leaders should be asking: Do we genuinely have the skills, processes and tooling to manage this system safely over time? If something goes wrong, will we detect it quickly, understand why, and know what to do next?

Where the answer is “not yet”, the committee still has options. It can keep AI in a decision-support role rather than fully automating decisions (for example, running parallel processing until the automated process has been sufficiently fine-tuned to reach approximate parity with human decisions). The oversight committee could ask for a staged rollout, starting with a tightly controlled pilot groups. It can limit the scope of the system to lower-risk processes or user groups, or decide to revisit the idea once capability, data quality or regulatory clarity have improved.

Finally, for AI governance to be more than a one-off hurdle, decisions need to translate into concrete commitments. That means clearly naming accountable owners, agreeing the actions required to put mitigations in place, developing an approach to pre-deployment testing and defining how performance and risk will be monitored over time. High-risk systems should come back to the committee on a regular cadence, armed with updated impact assessments, incident reports and real-world performance data. Over time, this creates a feedback loop that helps organisations to use AI safely and confidently in their own context.

Author:

James Calder Managing Director, National Cyber Lead

james.calder@scyne.com.au | LinkedIn